ALBERTO ORTEGA-TREJO

Mexican artist, researcher and architectural designer.

Get in touch by clicking here: ✉

His work uses architecture,

drawing, sculpture, writing and video to explore histories of indigeneity in architectural

modernity, the production of extreme environments, the spatial politics of the colonial encounters in North America and the architectures of social experiments. He has been

an IDEAS Fellow of the Society of Architectural Historians and a grantee of Jumex

Foundation for Contemporary Art, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and DCASE,

among others. His work has been shown at Prairie, DePaul Art Museum, BienalSur, Ca’ Foscari

Zattere, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Uri-Eichen Gallery, SpaceP11

and Centro de Arte y Filosofía. He has been a guest speaker for institutions and

organizations like DocTalks x MoMA for the Emilio Ambasz Institute, the American Institute

of Architects, the Society of Architectural Historians, Smart Museum of Art, Materia

Abierta, UPenn, MAS Context and CENTRO.

He is a lecturer of Architecture History and Studio at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Program Manager of the Katz Center for Mexican Studies at the University of Chicago and an Independent Spatial Designer.

UPCOMING:

La mitad de abajo: ecosistema en penumbras. Asamblea de Artistas y Activistas del Valle del Mezquital. Galería A4, Tlahuelilpan, Hidalgo. Oct 5, 2025, 1PM.

ARTIFICIAL-AGENCY

Architectural Consultancy

Exhibition Strategy

Research and Publication

Previous clients and collaborators include, Art Institute of Chicago, Singapore Art Museum, Edith Farnsworth House, Goethe-Institut Chicago, Michael Rakowitz Studio, Black Athena Collective, Dawit L. Petros, and Center for Latin American Studies at The University of Chicago.

Keep scrolling for selected projects ↆ

One of the qualities of nocturnal beings is that they speak words of truth

Solo exhibition at Prairie, Chicago

From the perspective of complementary opposites that set the cosmos in its dynamic motion, there is, for the Otomí, a primary division in the separation between day and night. “This day/night asymmetry is marked by the opposition between two paradigmatic figures”: one of them is the night, which belongs to the Devil, and to him, the half of the world where the Otomí people, his children, live. In the Otomí worldview, the Devil acts as the demiurge of their destinies, creating and undoing in the night.

(…) the conjunction and disjunction of the various entities that inhabit the body during the day are carried out at night, when they come out to frolic along the path of dreams, where they meet and part according to the circumstances; as it ritually happens during the celebration of Carnival: a hallucinatory ritual where a sort of “clinical history” (“pulse measurement” or “calibration of forces”) can be read. A way to identify and name the instances involved in the process of reorienting the world.

This solo exhibition at Prairie revolves around a metal sculpture that contains and displays a burning propane flame. The tube’s geometric configuration is an abstract rendition of the overall shape of oil and gas pipelines that have exploded between Mexico and the United States in the past decade. The presence of the fire evokes and makes present the catastrophic outcome of oil and gas pipelines along the Valle del Mezquital region (labeled by national authorities as Mexico’s "Environmental Hell"), the home territory of the Otomi, where a series of explosions and leaks have contributed to the already dire ecological collapse of ecosystems and communities in the region.

The controlled yet menacing presence of the propane tank and gas valves addresses the history of controlled fires along the pipelines, performed by the Mexican state as a spectacle of industrial and economic progress. This structure, which embodies the state’s desire for containment and control, rests on the floor of the gallery and is surrounded by charcoal drawings over cement panels portraying nocturnal creatures: an opossum, a ringtail, and a skunk. The animals display archetypal passions that are present in the nocturnal world of Otomí cosmology and geography. Such animals, and their abstraction in the realm of dreams, also act as advisors for nocturnal meditations.

The night, in its psychic and erotic excess, produces a field of possibilities for the transfiguration of the human—a place to shift species, to become a tree, a ringtail, a mountain, but also to shift gender, to shift scale, and be in a continued search to reorient our position in the world and to increase the possibilities of human becoming. In the back of the room, a hollow plastic rock supported by a metal arachnid exoskeleton acts as a beer cooler, directly addressing the history of alcoholism and alcohol use in Otomi communities, not only as a carrier of disease but also as a means of sustenance and ritualistic excess. At the bottom of the hollow rock, below ice and alcoholic beverages, a group of maguey skins rest, drowning but also rehydrating themselves, slowly decaying and festering new forms of life.

(…) the conjunction and disjunction of the various entities that inhabit the body during the day are carried out at night, when they come out to frolic along the path of dreams, where they meet and part according to the circumstances; as it ritually happens during the celebration of Carnival: a hallucinatory ritual where a sort of “clinical history” (“pulse measurement” or “calibration of forces”) can be read. A way to identify and name the instances involved in the process of reorienting the world.

This solo exhibition at Prairie revolves around a metal sculpture that contains and displays a burning propane flame. The tube’s geometric configuration is an abstract rendition of the overall shape of oil and gas pipelines that have exploded between Mexico and the United States in the past decade. The presence of the fire evokes and makes present the catastrophic outcome of oil and gas pipelines along the Valle del Mezquital region (labeled by national authorities as Mexico’s "Environmental Hell"), the home territory of the Otomi, where a series of explosions and leaks have contributed to the already dire ecological collapse of ecosystems and communities in the region.

The controlled yet menacing presence of the propane tank and gas valves addresses the history of controlled fires along the pipelines, performed by the Mexican state as a spectacle of industrial and economic progress. This structure, which embodies the state’s desire for containment and control, rests on the floor of the gallery and is surrounded by charcoal drawings over cement panels portraying nocturnal creatures: an opossum, a ringtail, and a skunk. The animals display archetypal passions that are present in the nocturnal world of Otomí cosmology and geography. Such animals, and their abstraction in the realm of dreams, also act as advisors for nocturnal meditations.

The night, in its psychic and erotic excess, produces a field of possibilities for the transfiguration of the human—a place to shift species, to become a tree, a ringtail, a mountain, but also to shift gender, to shift scale, and be in a continued search to reorient our position in the world and to increase the possibilities of human becoming. In the back of the room, a hollow plastic rock supported by a metal arachnid exoskeleton acts as a beer cooler, directly addressing the history of alcoholism and alcohol use in Otomi communities, not only as a carrier of disease but also as a means of sustenance and ritualistic excess. At the bottom of the hollow rock, below ice and alcoholic beverages, a group of maguey skins rest, drowning but also rehydrating themselves, slowly decaying and festering new forms of life.

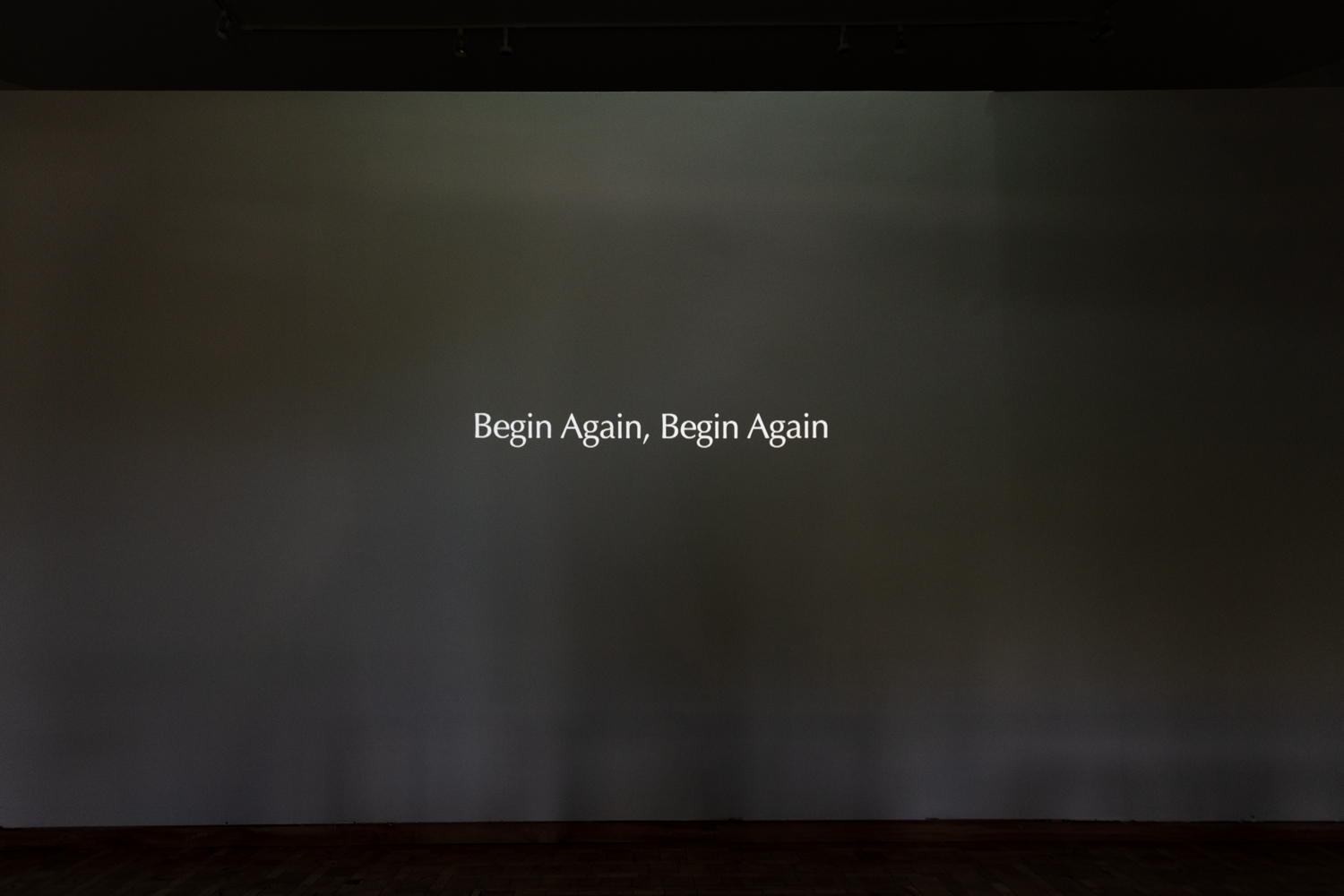

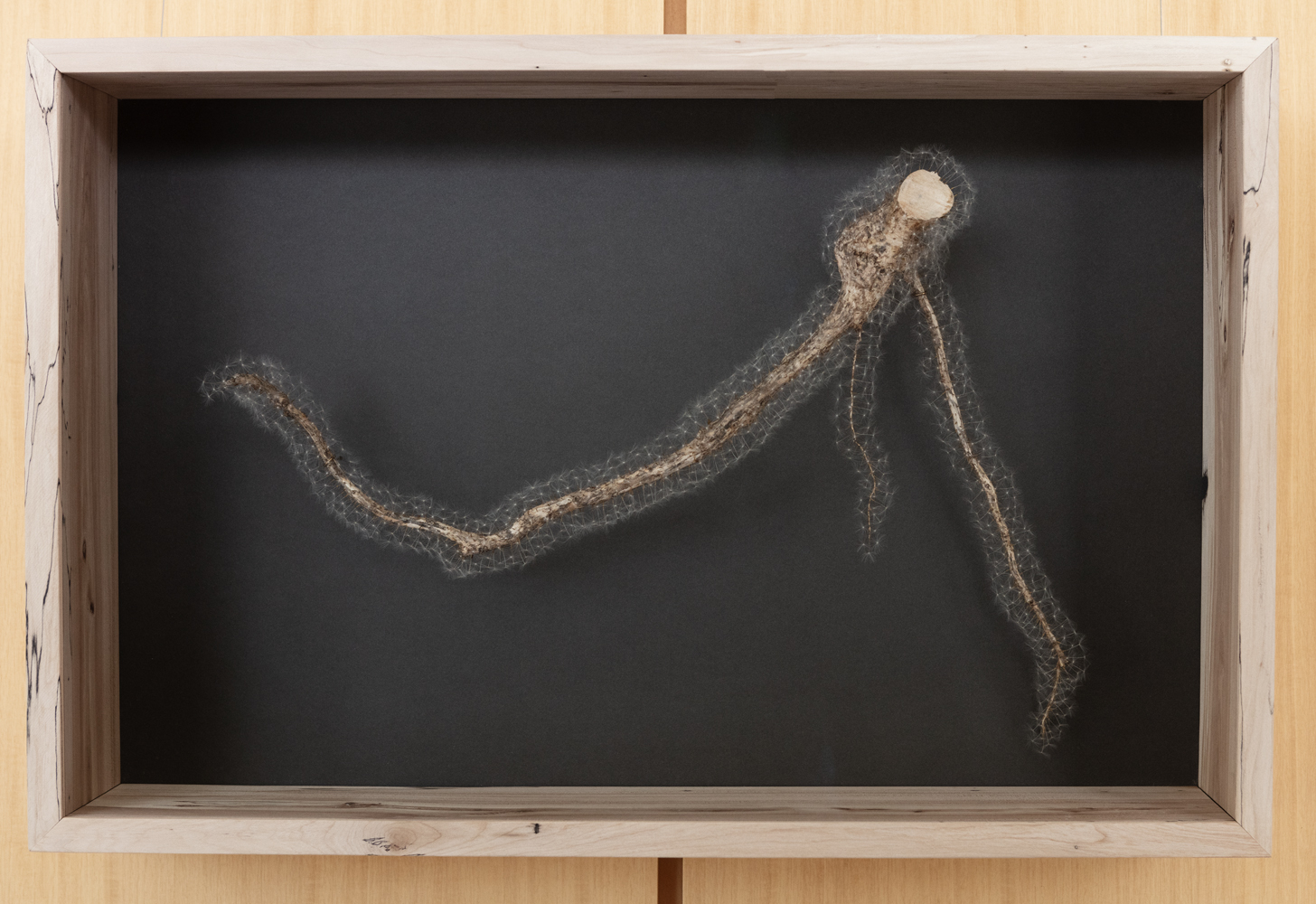

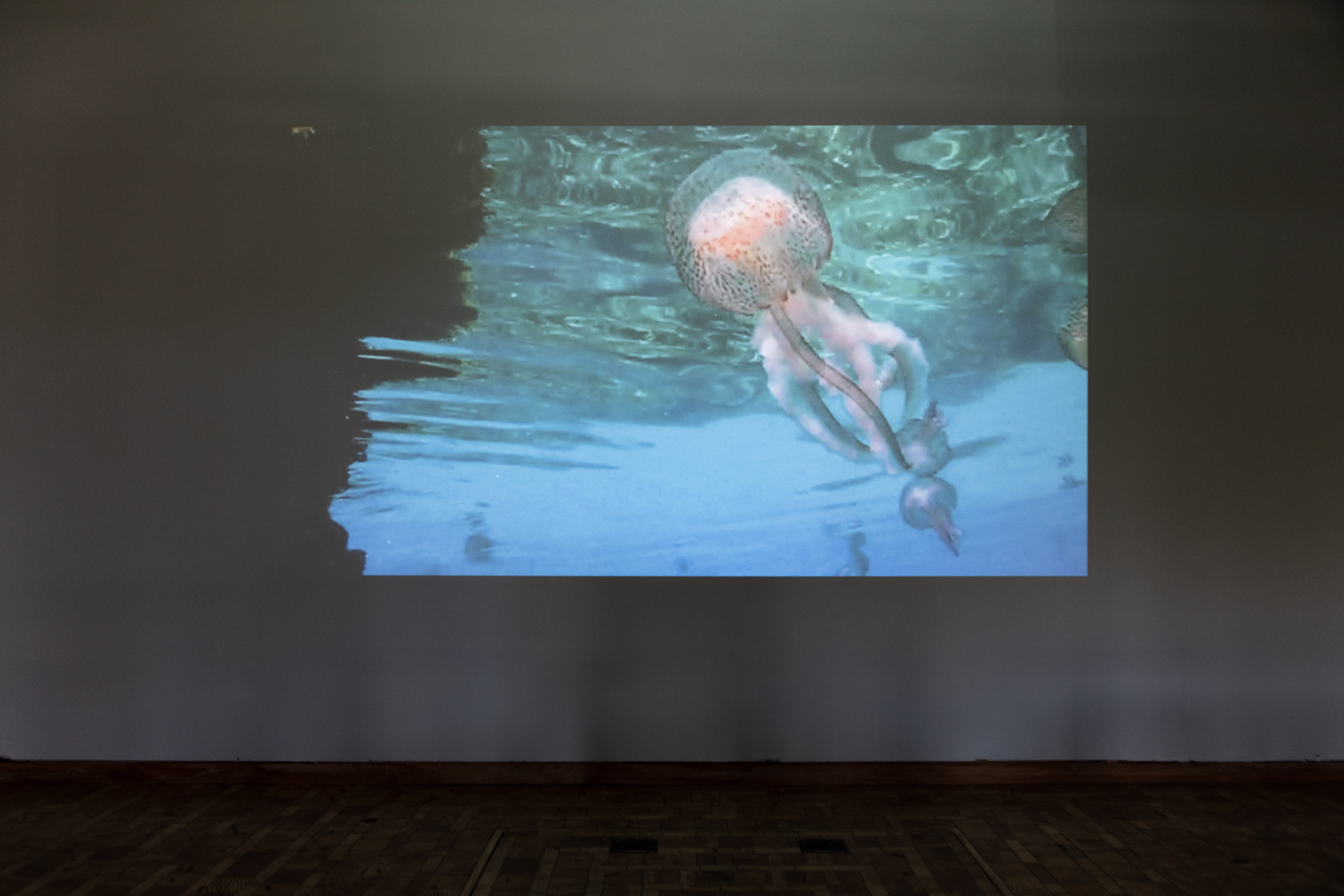

The Last of Animal Builders

At Mies van der Rohe’s Edith Farnsworth House

Curatorial Project

Artists: ASMA, Faysal Altunbozar, Selva Aparicio, Daniel Baird, Renée Green, Claudia Hart, Ragnar Kjartansson, Thiago Rocha Pitta, Joshi Radin & Michael Rakowitz.

Special thanks to Eden Manresa and Corcoran Industrial, for production assistance and to Gabriel Moreno of POCO Projects for exhibition fabrication and installation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Special thanks to Eden Manresa and Corcoran Industrial, for production assistance and to Gabriel Moreno of POCO Projects for exhibition fabrication and installation.

In 1970, a year before her passing, the eminent architecture critic Sibyl Moholy-Nagy penned a thought-provoking passage in "Chapter Three: Defenseless Breeders" from her unpublished manuscript, "Pragma." She boldly asserted that what truly distinguishes animal structures from their human counterparts is the seamless fusion of structure and space within the former. In the world of animals, structure isn't merely a means to bridge a functional void; it is the functional void itself, exemplified by the efficient structural designs of beehives, nests, and spiderwebs. Moholy-Nagy further underscored this notion by dubbing the renowned architects Mies van der Rohe and SOM as "The Last of Animal Builders," marking a stark departure from traditional architectural perspectives. With this declaration, she impelled us to delve into the intricate web of relations that intertwine the human experience with animals, nature, society, and the economy—architecture serving as the pivotal mediator and determinant. As we reinterpret the legacy of Mies van der Rohe through the prism of animality, Moholy-Nagy compels us to confront a multispecies ethics and politics, fundamental components in shaping our spaces and societies. Yet, her pronouncement of the end of animal logic within architectural modernity raises profound questions, hinting at the expectation that modern humans should transcend their animal condition. She posits architecture as the artificial matrix by which human societies refine their biological development. However, this argument inadvertently hints at a justification of modernity as an inevitable stage in evolution, thereby isolating it from its political dimensions.

At the heart of Moholy-Nagy's discourse lies a critical query: can we envision humanity as a chimeric entity, an organism capable of achieving limitless forms and configurations through the mediums of architecture, art, and technology? According to this line of thought, our humanity hinges on our capacity to fashion devices of chimerization—tools that enable not only survival but also transformation. These devices expand the horizons of our thinking, equip us to endure hostile environments, and even allow us to perceive and think through darkness. By aiming to think like other living organisms, we pave the way for a world where all potential intelligences can flourish.

Described as "defenseless breeders" by Moholy-Nagy, humans find their connection with fellow living organisms through a spectrum that ranges from mimicry and interdependence to, at its bleakest, exploitation and extraction. Drawing inspiration from the realms of animals, plants, minerals, and insects, we've molded our societies based on what we perceive as efficient interactions and behaviors. Regrettably, throughout the era of modernity and into our contemporary political landscape, the belief in the dichotomy between the human and the "natural" has done little more than exacerbate relations of exploitation rather than nurturing collaboration, coexistence, and mutually beneficial transformations.

This exhibition, inspired by Moholy-Nagy's radical explorations, turns the Edith Farnsworth House into a breathing organism. It showcases a curated selection of artworks from the Thoma Foundation's Art Collection, seamlessly blended with contributions from contemporary artists. These artworks collectively contemplate the profound impact of architectural modernity, minimalism, and capitalism on our perceptions of nature, humanity, non-human entities, and the economy. Spanning various mediums, including video installations, sculpture, and drawing, these works engage with the site's existing architecture, offering poignant reflections and poetics of destruction and regeneration. Speaking through plant, animal, and mineral metaphors, the artists delve into pressing social issues, the intricacies of human desire and transformation, our relationship with bodily fragility, and the complexities of thinking beyond the confines of anthropocentric power dynamics. Ultimately, this exhibition serves as an invitation to reimagine the intersecting realms of architecture, art, and human existence within an ever-evolving world.

At the heart of Moholy-Nagy's discourse lies a critical query: can we envision humanity as a chimeric entity, an organism capable of achieving limitless forms and configurations through the mediums of architecture, art, and technology? According to this line of thought, our humanity hinges on our capacity to fashion devices of chimerization—tools that enable not only survival but also transformation. These devices expand the horizons of our thinking, equip us to endure hostile environments, and even allow us to perceive and think through darkness. By aiming to think like other living organisms, we pave the way for a world where all potential intelligences can flourish.

Described as "defenseless breeders" by Moholy-Nagy, humans find their connection with fellow living organisms through a spectrum that ranges from mimicry and interdependence to, at its bleakest, exploitation and extraction. Drawing inspiration from the realms of animals, plants, minerals, and insects, we've molded our societies based on what we perceive as efficient interactions and behaviors. Regrettably, throughout the era of modernity and into our contemporary political landscape, the belief in the dichotomy between the human and the "natural" has done little more than exacerbate relations of exploitation rather than nurturing collaboration, coexistence, and mutually beneficial transformations.

This exhibition, inspired by Moholy-Nagy's radical explorations, turns the Edith Farnsworth House into a breathing organism. It showcases a curated selection of artworks from the Thoma Foundation's Art Collection, seamlessly blended with contributions from contemporary artists. These artworks collectively contemplate the profound impact of architectural modernity, minimalism, and capitalism on our perceptions of nature, humanity, non-human entities, and the economy. Spanning various mediums, including video installations, sculpture, and drawing, these works engage with the site's existing architecture, offering poignant reflections and poetics of destruction and regeneration. Speaking through plant, animal, and mineral metaphors, the artists delve into pressing social issues, the intricacies of human desire and transformation, our relationship with bodily fragility, and the complexities of thinking beyond the confines of anthropocentric power dynamics. Ultimately, this exhibition serves as an invitation to reimagine the intersecting realms of architecture, art, and human existence within an ever-evolving world.

Agua Muy Vieja Del Lugar Espantoso

At Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago

As part of Gentle Content, a group show curated by Julia Birka-White

“Alberto Ortega Trejo’s contributions to Gentle Content were

prompted by recent news events that illuminate class struggles — specifically in his home country of Mexico — in addition to his research regarding Indigenous Mexican cosmologies. When

creating these new objects, Ortega Trejo considered the deadly 2019

explosion in Tlahuelilpan, Mexico of a pipeline owned by Pemex,

the state oil company. The illegal extraction, possession, and sales

of thefted fuel has been a long standing issue in the country, the

result of larger class and economic disparities affecting sites of

mineral extraction and oil processing as is the case of Tlahuelilpan,

an Otomí territory. Ortega Trejo’s metal figurative cut-outs adhere

to the wall, and similar to Bredar’s painted suspended heads are disjointed and cut off from their whole. Discernable is an

amputated leg referencing the overcirculation of violent image in contemporary Mexico while engaging with Otomí God-making

practices. Next to it, a nebulous form that is actually an alcohol

sack, hovers among other silhouettes. The alcohol sacks the artist

is referencing are used for pulque (a traditional Mexican alcoholic

drink of fermented agave nectar) storage and typify the effect of alcoholism on colonized Indigenous communities globally.

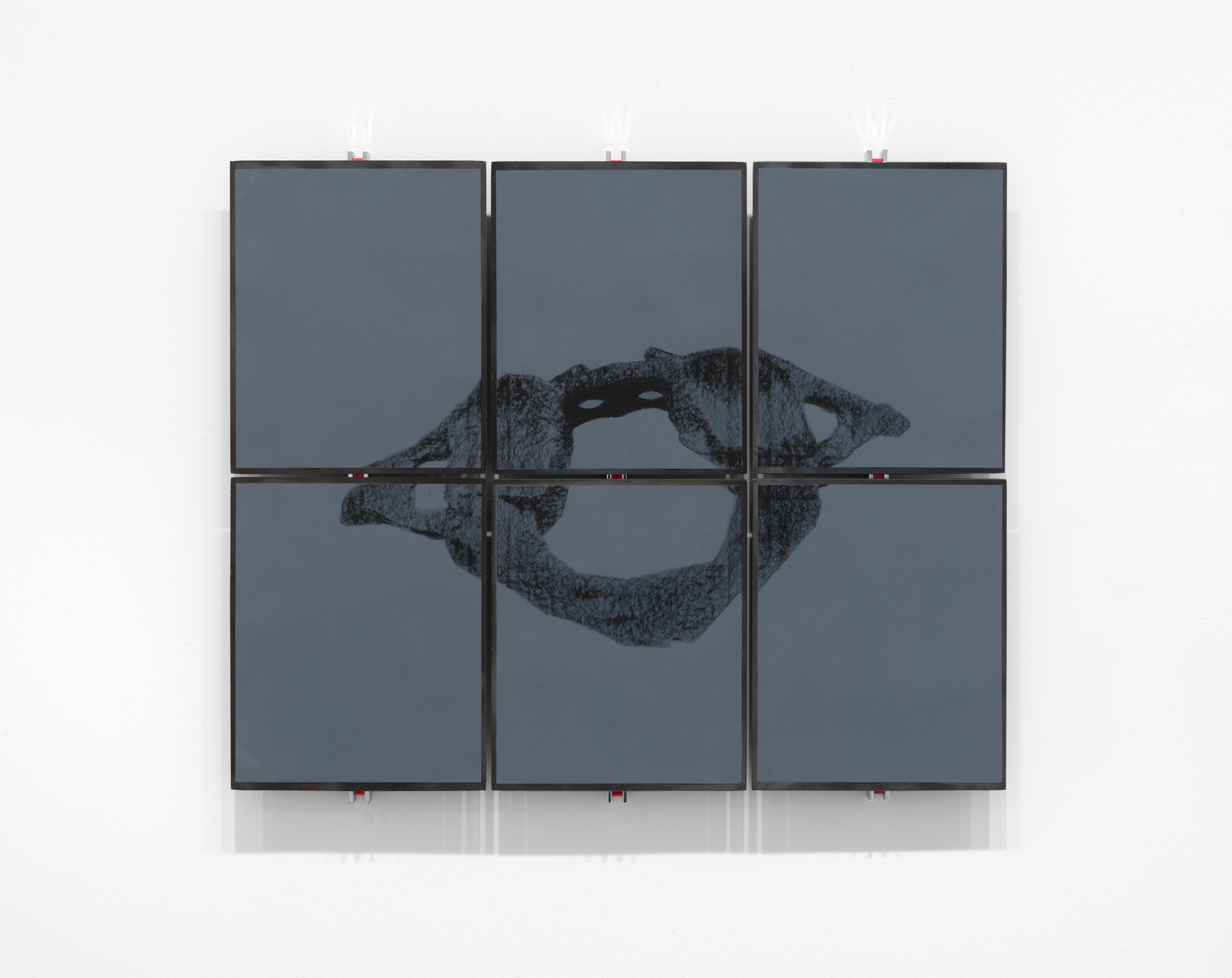

Additionally, six charcoal on sandpaper drawings mounted on

metal plates and organized in a grid unite to form an atlas bone.

Interested in bones and the practice of their display in sacred and

communal spaces in Central Mexico as well as in their political and

forensic register, Ortega Trejo’s precise drawing could be read as a

warning or a sign of perpetuation and regeneration.”

Julia Birka- White, Director of Rhona Hoffman Gallery

Julia Birka- White, Director of Rhona Hoffman Gallery

Las Aguas Bajan Turbias

For BienalSur

On Otomí labor and territories, pollution and Mexico City’s Sewage system

With Andrea Hunt

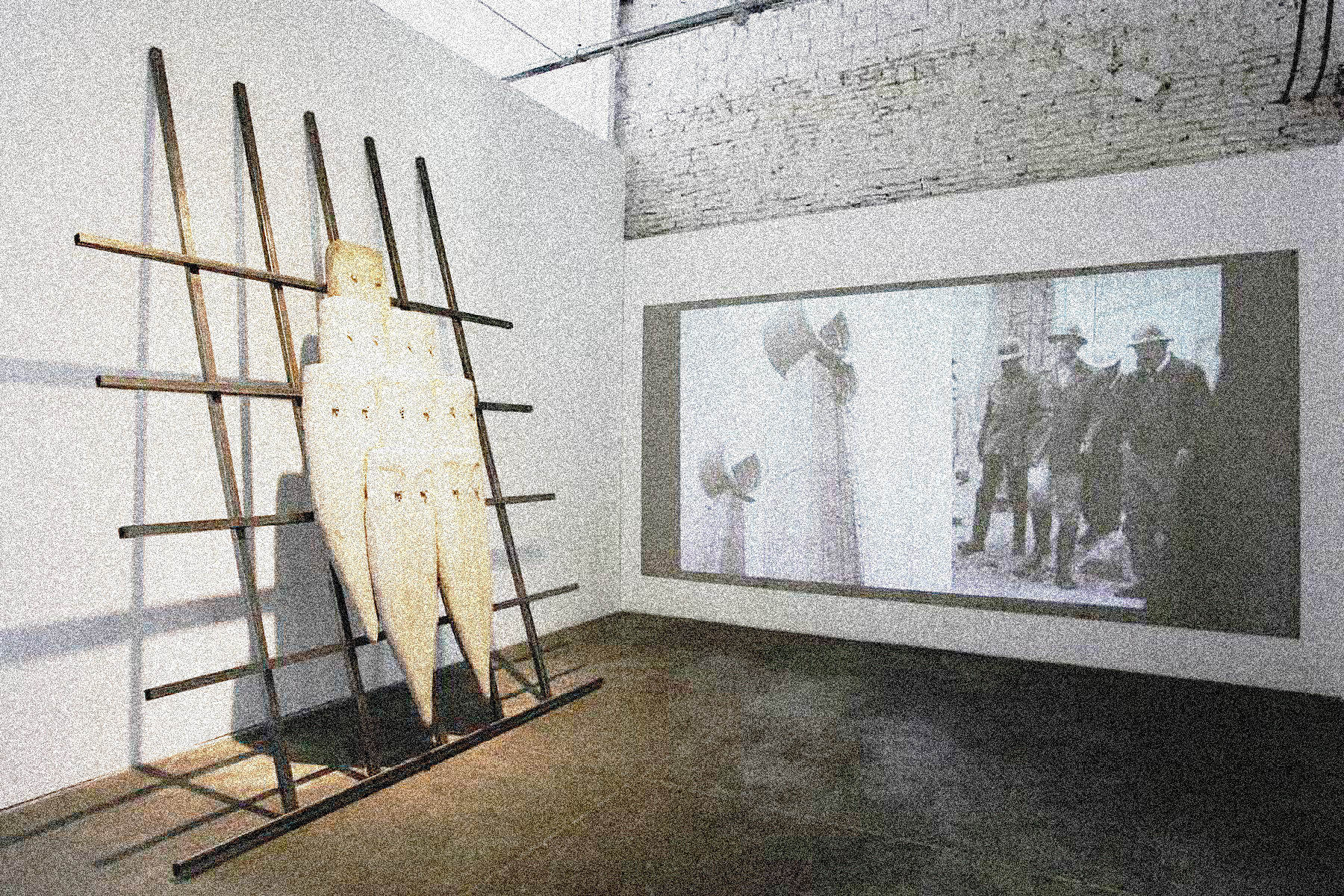

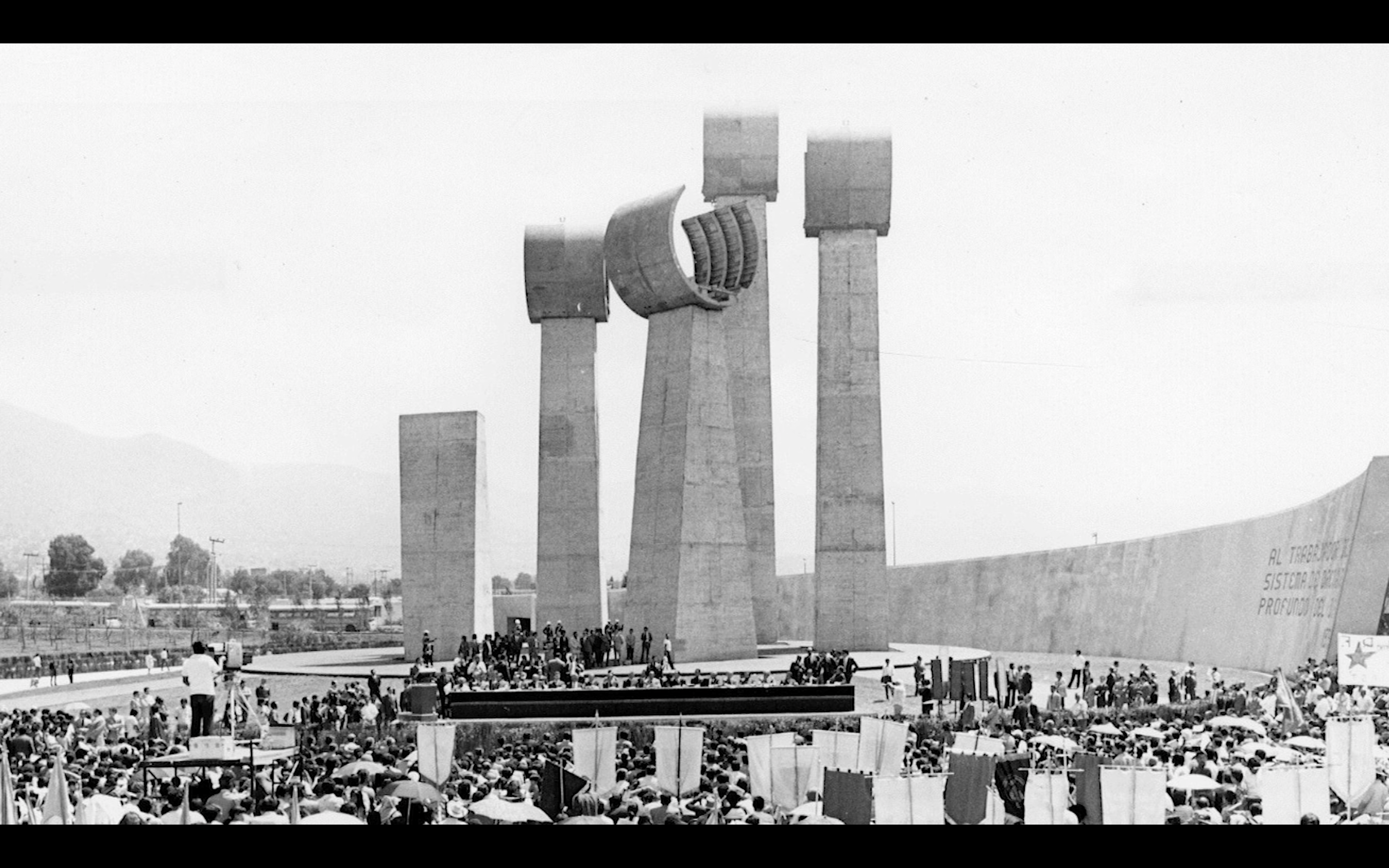

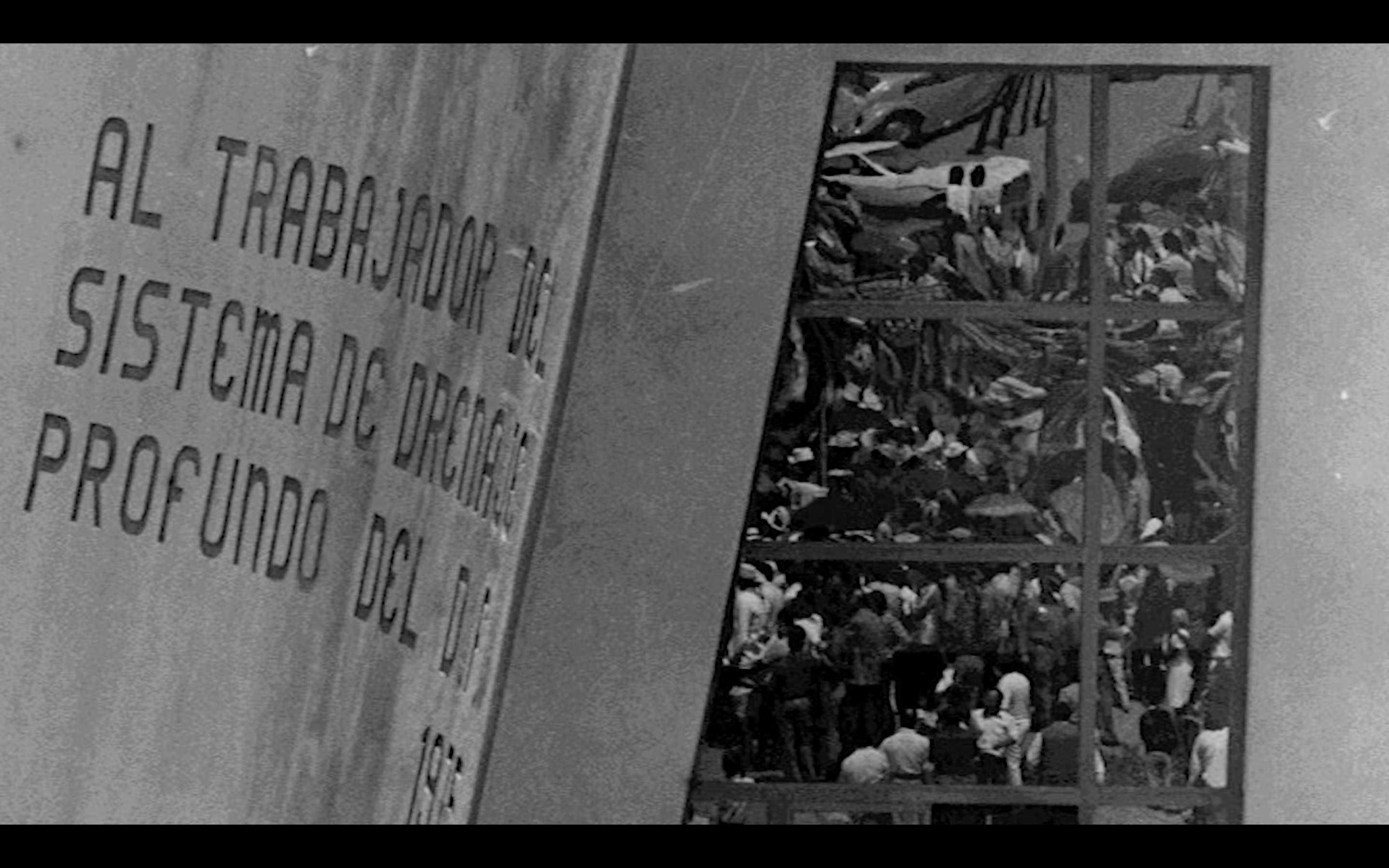

This exhibition is comprised of El Mundo Debajo and El Espejo Otomí. El Mundo Debajo is an experimental documentary that traces the Mexican Modern state’s representation of indigeneity through the making of Mexico City’s sewage system. The video is projected over four prefabricated concrete panels. El Espejo Otomí is a sculpture consisting of eight concrete casts of a maguey leaf acting as a cladding system for a metal structure. This fragment takes a traditional building method of the Otomi region in Hidalgo to the material language of modernity. The Otomí region receives Mexico City’s black waters and has been historically exploited for minerals for the production of cement, a key element for the infrastructural transformations of Mexico City. This work was produced for BienalSur, curated by Leandro Martinez Depietri and Benedetta Casini and installed at Fundación Andreani in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The research for this project was funded by the American Institute of Architects and MIT’s Global Architecture History Teaching Collaborative.

This exhibition is comprised of El Mundo Debajo and El Espejo Otomí. El Mundo Debajo is an experimental documentary that traces the Mexican Modern state’s representation of indigeneity through the making of Mexico City’s sewage system. The video is projected over four prefabricated concrete panels. El Espejo Otomí is a sculpture consisting of eight concrete casts of a maguey leaf acting as a cladding system for a metal structure. This fragment takes a traditional building method of the Otomi region in Hidalgo to the material language of modernity. The Otomí region receives Mexico City’s black waters and has been historically exploited for minerals for the production of cement, a key element for the infrastructural transformations of Mexico City. This work was produced for BienalSur, curated by Leandro Martinez Depietri and Benedetta Casini and installed at Fundación Andreani in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The research for this project was funded by the American Institute of Architects and MIT’s Global Architecture History Teaching Collaborative.

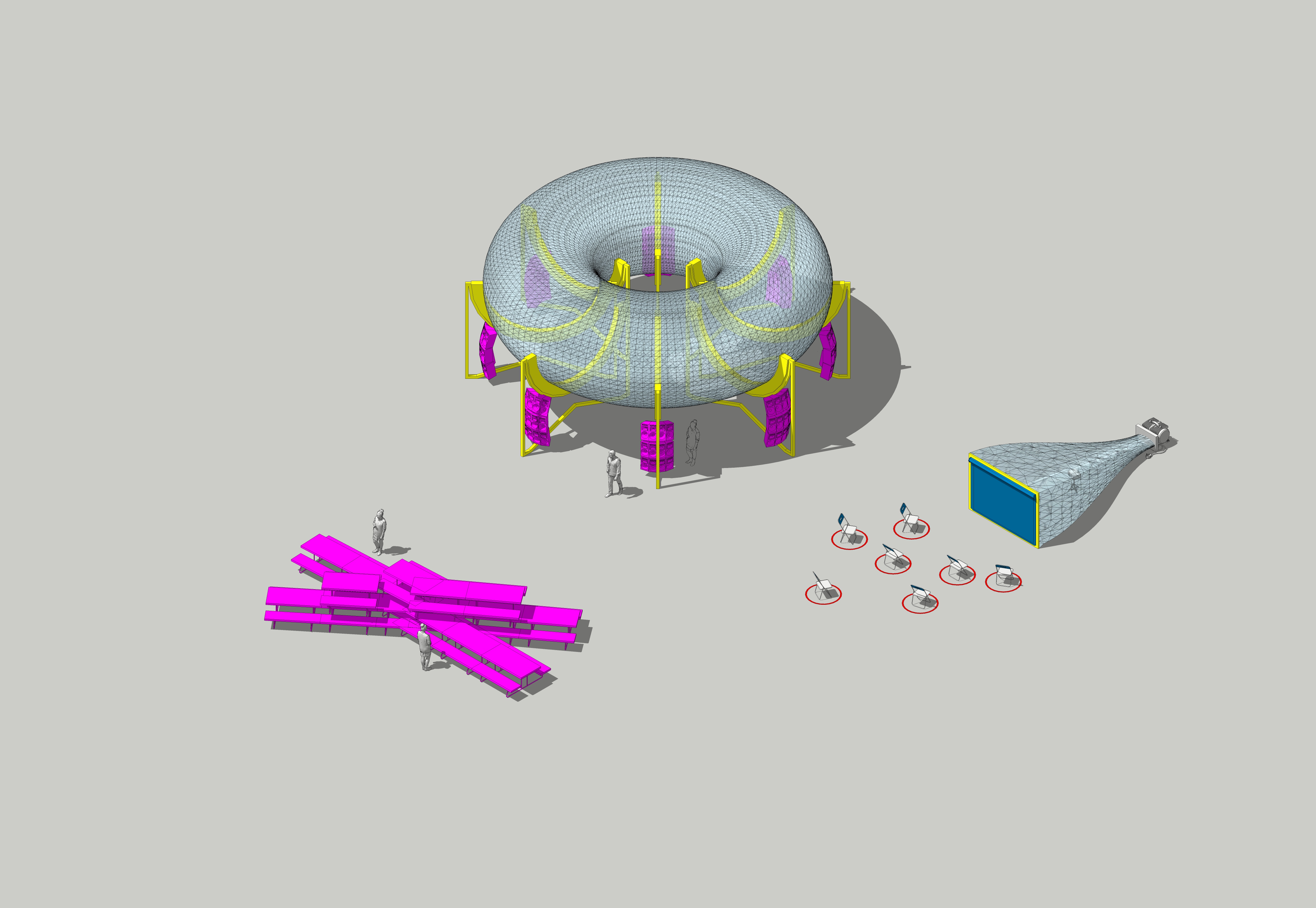

Media Stations for Pilsen

W/ Inga

Exhibition Strategy and Public Space Intervention

Media Stations for Pilsen is a series of three urban scale sculptural platforms that will allow the Pilsen community to create and engage in outdoor artistic and leisure events during the Summer of 2021. Each Media Station will center on a specific sensorial quality to be the main focus for the content and events it will host: Sonic, Visual and Tactile.

The Sonic Station is a mobile sound system that will host listening sessions curated by artist Eduardo F. Rosario, block parties, karaoke sessions and sonideros programmed by neighbors and community members.

The Visual Station consists of a mobile screening platform that will be used for outdoor lectures, artist talks and movie screenings curated by Pilsen based cineclub filmfront.

The Tactile Station is an outdoor working table and meeting place to host reading groups, random encounters and artist led workshops coordinated by Pilsen based publishing platform Inga.

Each station can stand alone and be combined to allow multimedia experiences.